Cyber War in Ukraine: Hacktivism or State-Sponsored Spying?

Hacker activism and the cyber war in Ukraine entered a dangerous new phase in early 2022 when a group styling itself ‘Belarusian Cyber Partisans’ claimed responsibility for sabotaging railways to slow the transfer of Russian forces into the war-ravaged country.

Modern hacktavists

The hacker activists - ‘hacktavists’, as they’re called - added a threat: “The internal network will be disconnected until the Russian troops leave the territory of Belarus and the participation of the Belarusian military forces in the fascist aggression ceases.”

When Ukraine's government called for a volunteer 'IT Army', the cyber world responded but the combination of cyber warriors without a leader and Russia’s boots-on-the-ground invasion of Ukraine could have chilling consequences worldwide. An estimated 400,000 hackers from 50 groups including Anonymous have injected themselves into a deadly war with a nuclear superpower.

“This shocking act by Russia has brought together the technology community in ways I have never seen,” said Kevin McDonald, a SPYEX consultant and expert in cybersecurity. “That community has many facets of which hacktivists are one. There is no doubt that unanimity of purpose has arisen in the world of purist hackers, hacktivists, and separately cyber-criminals.”

"The brand new social experience where you activate your gaming skills as you train like a spy."

- TimeOut

Take on thrilling, high-energy espionage challenges across different game zones.

What is hacktivism?

Hacktivism was once the preserve of key punchers defacing websites or infecting computer worms with jokey names like ‘Wank’ as a political protest back in the 1980s.

Hacktivists didn’t break into computer systems to steal. They were there to make a point.

Anti-nuclear activists in Australia unleashed ‘Worms Against Nuclear Killers’ in 1989, targeting NASA and the US Department of Energy to protest the launch of a shuttle carrying radioactive plutonium.

By the mid-1990s, Hacktivists were experimenting with denial-of-service (DoS) attacks to topple their online targets. They would jam a computer system with traffic - known as junk packets - until the server gave in and the computer or website crashed.

Hacktivism comes of age

‘The Zippies’ - essentially cyber hippies - organized an ‘email bombing’ campaign to clog British government accounts in 1994. The protest targeted a proposed law that would outlaw outdoor raves, dance festivals, and ‘music with a repetitive beat’. The ‘Intervasion’, as it became known, reportedly shut down UK government computers for a week.

Things took a nasty turn when a group calling itself Internet Liberation Front hacked IBM and Sprint, installing a program that sent email messages every few seconds. ILF’s manifesto railed against what they termed ‘capitalist pig’ corporations. The ILF also left a threat for the companies: "Just a friendly warning corporate America; we have already stolen your proprietary source code. We have already pillaged your million-dollar research data. And if you would like to avoid financial ruin, get the f*** out of Dodge. Happy Thanksgiving Day turkeys."

Strano Network hacktivists

Hacktivism spread quickly. By 1995, the Strano Network was organizing a one-hour ‘Net strike’ against French government websites to protest nuclear and social policies.

In one of the first defacements of a website in 1996, hackers changed the US Department of Justice website to read ‘Department of Injustice’ and posted pornographic images to protest the Communications Decency Act, which prohibited individuals from knowingly transmitting obscene or indecent messages to a recipient under 18. (The law was later ruled unconstitutional for violating free speech.)

Cult of the dead Cow

The Cult of the Dead Cow (cDc), the group that coined the term Hacktivism, was born in Texas in 1984 and named after a nearby slaughterhouse. By the 1990s, they were making international headlines for building Back Orifice, a trojan intended to show the flaws of Microsoft Windows 98. Apparently they’re still at it, hacking Windows 7, Windows XP, and Vista.

Hackers and cyber war

Hackers worldwide took to their keyboards during the war in Kosovo in 1998 and 1999. TeamSploit wrote “stop the war” on the US Federal Aviation Authority’s website. The Russian Hackers Union wrote “stop terrorist aggression” on a US Navy site, and the Serb Black Hand Group (Crna Ruka) is believed to have been behind a DoS attack on NATO.

Hackers who claimed to operate in mainland China joined the online war to target US government websites after the bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999. The White House shut down www.whitehouse.gov for three days, reportedly because of a non-stop denial-of-service attack.

The late 90s also saw the birth of the New York activists known as Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT), a hybrid mix of art, radical politics and a software tool called FloodNet to flood government and company web pages. EDT took over sites in virtual ‘sit ins’ to protest policies relating to globalization and capitalism.

Hacktivism as a political tool

By the time of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York’s World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001, thousands of new groups and alliances were forming. The Young Intelligent Hackers Against Terrorism claimed to penetrate the computer systems of two Arabic banks with ties to Osama bin Laden, although the banks denied it. Meanwhile, GForce Pakistan proclaimed an ‘Al-Qaeda Alliance Online’ to pledge support for bin Laden and target US and British websites.

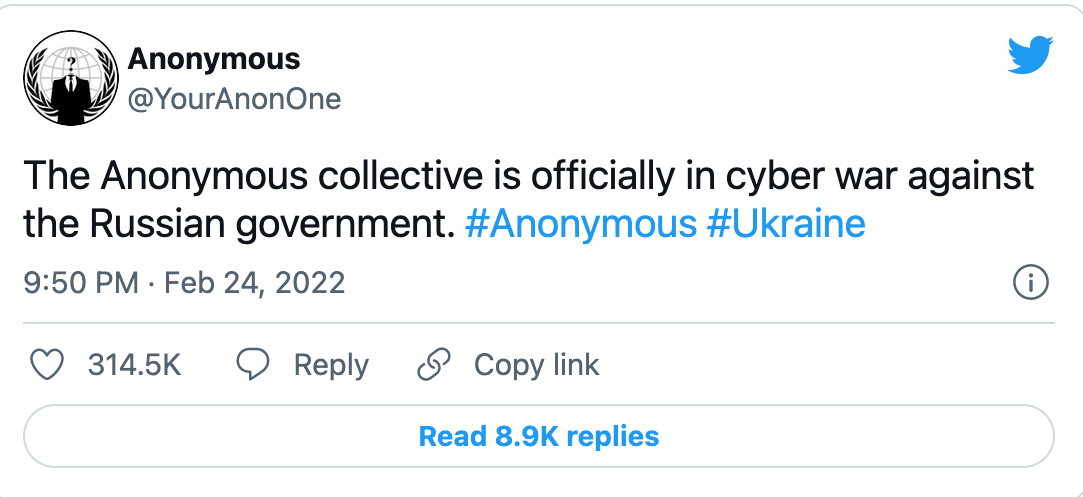

Anonymous emerged from the 4chan online messaging board in 2003 and drew attention with Project Chanology in 2008, essentially a war against the Church of Scientology who they accused of censoring a video of Tom Cruise praising the church. Anonymous - which is a loose collective rather than an organized gang - has launched hundreds of operations in the two decades since then including defacing websites during the Arab Spring in 2011, Operation Hong Kong in 2014, and pro-Taiwan hacks in 2020 on the UN's website.

State-sponsored hacktivism

As thousands of hacktivists and new groups emerged, a new trend evolved: the state-sponsored hacktivists, governments masquerading as citizen hacktivists or directing citizen hackers to insert themselves into politics or global conflicts.

The Russian government is believed to have been behind NotPetya, a data-wiping virus that targeted Ukraine In 2017, and for previous cyber attacks against Estonia and Georgia in 2008. North Korea was blamed for the hack of Sony Pictures in 2014 to stop the release of a comedy movie, The Interview, which outlined plans to assassinate Kim Jong-un. The US tightened sanctions against North Korea as a result.

Oil giant Saudi Aramco was also crippled by a cyber warfare attack linked to Shamoon malware in 2012 - which at the time was the biggest hack in history. Within hours, more than 30,000 computers were destroyed or partially wiped. Gasoline tank trucks lining up for refills had to be turned away because there was no way to pay. Ten percent of the world's oil was suddenly at risk. Iran’s Cutting Sword of Justice claimed responsibility and some believe the Iranian government assisted.

Cyber war in Ukraine

Fast-forward a decade and another worrying trend is emerging as the Russian-Ukraine war draws the attention of three once-distinct cyber groups: purist hackers, hacktivists, and cyber-criminals who hack into systems with threats to destroy files unless a ransom is paid. The Russia-Ukraine war is bringing the tech community together and there is a possibility that the cyber attacks could spread globally if more countries get involved.

McDonald isn't overly concerned about Anonymous attacking infrastructure in the US because that type of attack isn't aligned with the collective's stated goal of punishing injustice. He has another fear, however.

"We should be far more concerned about Russia and its own citizen cyber warriors coming for our infrastructure," he said. "Russian threat actors were attributed to be responsible for the vast majority of highly successful global Ransomware attacks in recent years. If they change from Ransom to destruction, it could get seriously ugly really fast."

There is evidence, for example, that Russian actors have already moved to wiping systems rather than encrypting them. Recovery in many instances, without paying the ransom, is impossible.

"If they choose to destroy and walk away the proverbial bodies of businesses and government left in their wake will be potentially earth-shattering. We know for a fact that Russia and China are both probing and entering our critical systems with impunity and can do real damage if they chose to do so."

SPYSCAPE+

Join now to get True Spies episodes early and ad-free every week, plus subscriber-only Debriefs and Q&As to bring you closer to your favorite spies and stories from the show. You’ll also get our exclusive series The Razumov Files and The Great James Bond Car Robbery!

Gadgets & Gifts

Explore a world of secrets together. Navigate through interactive exhibits and missions to discover your spy roles.

Your Spy Skills

We all have valuable spy skills - your mission is to discover yours. See if you have what it takes to be a secret agent, with our authentic spy skills evaluation* developed by a former Head of Training at British Intelligence. It's FREE so share & compare with friends now!

* Find more information about the scientific methods behind the evaluation here.

Stay Connected

Follow us for the latest

TIKTOK

INSTAGRAM

X

FACEBOOK

YOUTUBE