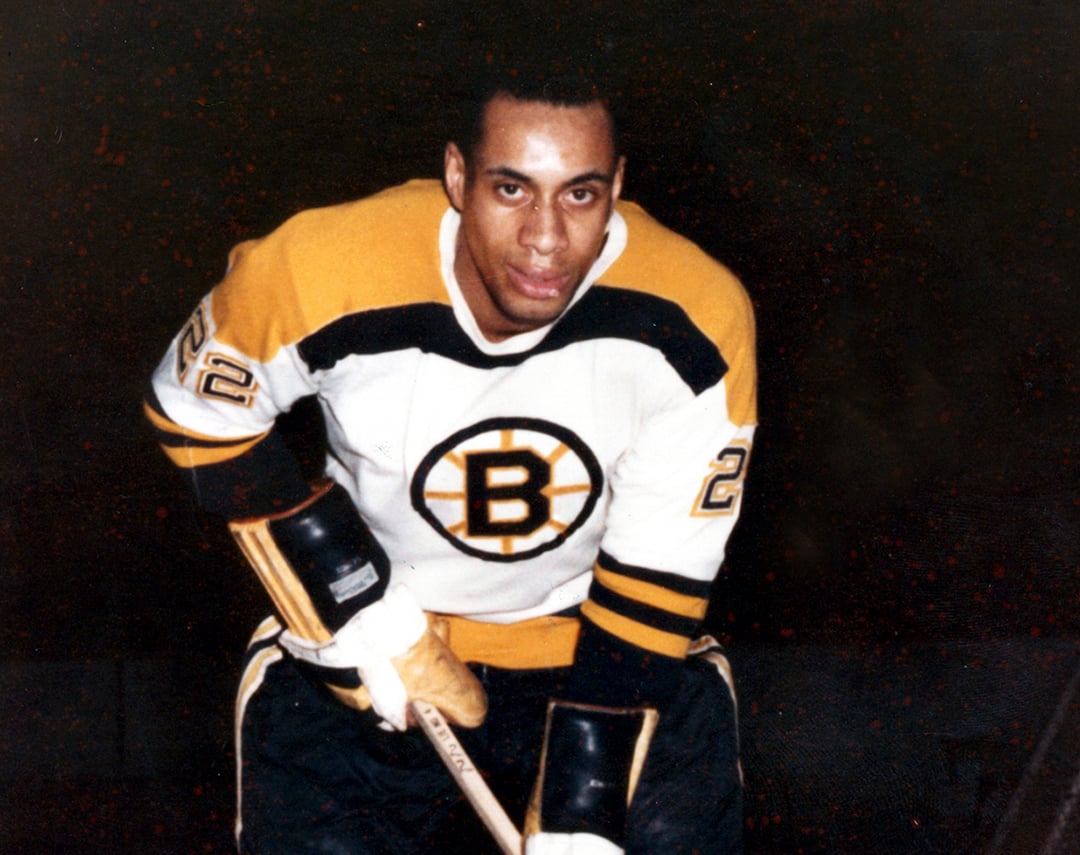

Willie O’Ree : The One-Eyed Secret Superhero of the NHL

When Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball, it was international news and cemented his position as one of sport’s most enduring figures. When Willie O’Ree broke the color barrier in hockey, there were no plaudits and no headlines, and his pioneering achievements went unrecognized for forty years. O’Ree is a Secret Superhero in more ways than one, though, as he also managed to conceal an incredible secret that should have prohibited him from playing at all.

One eye on the majors

Willie was born in Fredericton, New Brunswick, in 1935, and fell in love with Canada’s national sport at a young age. He first began skating aged three; his father would flood their backyard and create an impromptu rink for him to skate on. He was playing hockey by the age of five, and despite the O’Rees being one of only two black families in the town of Fredericton, Willie did not experience much racism in his early years on the ice. As he would later say, “when I was a little boy, all I knew was that hockey was my life, and that ‘black’ meant the puck, and ‘white’ meant the ice.”

"The brand new social experience where you activate your gaming skills as you train like a spy."

- TimeOut

Take on thrilling, high-energy espionage challenges across different game zones.

His early years involved other troubles. He broke an opponent’s collarbone with a check in a school game, the unfortunate boy turned out to be the son of the school hockey coach and Willie was subsequently kicked off the team. This did not hold him back, and his enormous talent led to him being signed up for the Kitchener-Waterloo Junior Canucks, a farm team for the Montreal Canadiens. His coach had high hopes for Willie, who was renowned as one of the fastest players of his generation on the ice, but those hopes seemed to have been cruelly dashed by an injury during a game in 1955. Willie was checked near the goal just as a teammate was taking a wild slapshot, the check spun Willie around and the puck caught him flat in the eye socket. In the hospital, he was given the worst news possible; the eye socket had shattered, and he had lost 97% of vision in his right eye. He would never play hockey again.

Concentrate on what you can see

Willie had two dreams; to be a professional hockey player, and to compete in the NHL. As a left winger, the loss of vision in his right eye was catastrophic, but Willie refused to give up on his ambitions, and learned to adapt. As he later said, he told himself “forget about what you can’t see and concentrate on what you can see”, and despite his greatly enlarged blindside he found - with some adaptation and largely thanks to his remarkable skating speed - he was still able to be highly competitive. At the end of the season, he got a call up from the Quebec Aces, who were the top professional team in the region at the time. Given an opportunity to realize one of his career ambitions, he simply did not tell them that he was blind in one eye. Nobody else noticed there was a problem; and the Aces went on to win the Quebec Hockey League that season, with Willie playing 83 games and scoring 23 goals.

The following season, he realized his second ambition. He had attended a training camp in Boston at the start of the 1957-58 season, and later that year the Bruins called him up as injury cover, and on January 18th, 1958, he made his debut for the Bruins at the Montreal Forum, a venue he knew well. The Bruins were underdogs but won 3-0, and very little fuss was made about O’Ree’s presence on the ice. Indeed, according to Willie, it only occurred to him the following day that he had made NHL history as the league’s first black player. He had not told the Bruins staff about his eye, as the NHL prohibited one-eyed players from participating. With his secret undiscovered, he returned to the ice the following day in a 6-2 loss, and, having both achieved history and successfully concealed his disability, he returned to his old club, certain that the Bruins would be contacting him again.

Return to Boston

In December of 1960, the anticipated call from Boston came, and this time they wanted Willie as a starter. He played 43 games for the Bruins that season, and firmly established himself as a fan favorite with the Boston support. He scored his first goal in January 1961, at Boston Garden versus the Canadiens, and the fans responded with a standing ovation that lasted for two full minutes. Unfortunately opposition fans - and players - were less welcoming, and he experienced appalling racist abuse throughout the season, especially when he faced the other three US based teams in the league. One game in particular stands out, against the Chicago Black Hawks, when Eric Nesterenko repeatedly threw racial slurs at Willie, before butt-ending him and knocking out two of WIllie’s teeth. As O’Ree would later say, if he had dropped his gloves every time he heard a racial slur “he knew that he’d be in the penalty box all the time”, but here Willie retaliated, bringing his stick down on Nesterenko’s head and inflicting a wound that required seventeen stitches. The Chicago fans were incensed, and as both sets of players joined the ensuing melee it seemed that the fans would also spill over onto the ice. O’Ree was taken off the ice and locked in the dressing room, “a prisoner in Chicago Stadium”, while stewards attempted to restore order.

At the end of the season, Willie was told he was being traded to the Canadiens, but they Montreal side sent him back to the minor leagues without so much as a tryout, a decision which Willie would later allege was motivated by racism. He would never figure in the NHL again, but continued playing minor league hockey into his 40s, spending the majority of his career in the Western Hockey League for sides in Los Angeles and San Diego. He continued to endure racist abuse throughout his career, but unlike his counterpart in baseball, Jackie Robinson, he was never lauded during his career as the player who broke the color barrier, not least because there had not been another black player in the NHL until the year he retired, 1974. It would take a while longer for O’Ree’s pioneering impact to be felt.

Belated recognition

After retiring, Willie settled in San Diego, where he worked first as a used car salesman, and later as a hotel security guard. Meanwhile, the NHL slowly caught up, as a handful of players of color slowly began to change the complexion of the league, a process that was accelerated by the league’s expansion from the Original Six teams of Willie’s era to the swollen ranks of the modern NHL. As the league grew larger the NHL became increasingly aware of the need to improve diversity within the sport, and so in 1998 they finally turned to their own Jackie Robinson to help with this effort. Willie was only too happy to oblige, and has spent the last quarter of a century as the NHL’s Diversity Ambassador, traveling the length of North America to encourage children from all backgrounds to take up the sport. He has been highly successful in this endeavor, with players of color now a common sight in the NHL, and the accolades he has belatedly received in later life have been as much to do with his work as an inspirational figurehead as his time on the ice.

The accolades may have been slow to arrive, but the good news is that people are finally starting to recognise Willie’s contributions. The Boston Bruins have retired his shirt number, 22, and appropriately in 2022 President Biden awarded O’Ree the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor the US can bestow on a civilian. O’Ree is the only NHL player in history to have been given this award, and this seems a fitting capstone on the remarkable career of a Secret Superhero who has spent the majority of his life performing remarkable deeds, both on and off the ice, in obscurity.

SPYSCAPE+

Join now to get True Spies episodes early and ad-free every week, plus subscriber-only Debriefs and Q&As to bring you closer to your favorite spies and stories from the show. You’ll also get our exclusive series The Razumov Files and The Great James Bond Car Robbery!

Gadgets & Gifts

Explore a world of secrets together. Navigate through interactive exhibits and missions to discover your spy roles.

Your Spy Skills

We all have valuable spy skills - your mission is to discover yours. See if you have what it takes to be a secret agent, with our authentic spy skills evaluation* developed by a former Head of Training at British Intelligence. It's FREE so share & compare with friends now!

* Find more information about the scientific methods behind the evaluation here.

Stay Connected

Follow us for the latest

TIKTOK

INSTAGRAM

X

FACEBOOK

YOUTUBE