Bennet Omalu: The True Superhero Who Fought the NFL and Won

When Bennet Omalu discovered evidence of a serious degenerative neurological condition affecting retired American football players, he believed that the NFL would welcome his findings and work with him to better protect their stars from this terrible disease. The reality was very different, as he was dismissed, insulted, and ignored by an organization that is not well known for its love of constructive criticism. After many years of struggle, Dr. Omalu has succeeded in getting the NFL - and the wider world of sport - to acknowledge the realities of the harm caused to athletes by repeated concussive injuries and, in the process, brought enormous relief to those affected and improved protection for future generations of athletes, a superheroic effort in the face of formidable opposition.

An intellectually competitive childhood

Bennet was born in 1968 in what was known at the time as Biafra, a breakaway region of Eastern Nigeria. The country was being torn apart by the ravages of a civil war and Bennet’s parents had been displaced; Bennet was born in a ramshackle hospital while his father was in a nearby ward, fighting for his life against an unknown ailment. Happily, his father recovered within two weeks of seeing his newborn son, and when the war ended two years later the Omalu family was able to return to their village of Enugwu-Ukwu, in southeastern Nigeria.

"The brand new social experience where you activate your gaming skills as you train like a spy."

- TimeOut

Take on thrilling, high-energy espionage challenges across different game zones.

Despite the outbreak of peace, Bennet’s childhood was still filled with difficulties. He suffered from depression from an early age and has talked of how his low self-esteem affected him in many ways. One consequence was that it made him - as he phrases it - intellectually competitive, and in a bid to prove his worth both to himself and others he threw himself into his studies. This proved to be a double-edged sword; he enrolled in medical school at just 16 years of age, but depression and self-doubt proved overwhelming and he dropped out shortly afterward. It would take some time for Bennet to become Dr. Omalu, but he eventually conquered his demons and graduated with a degree in medicine and surgery in 1990, aged 24. After a few years working as a doctor in the Nigerian city of Jos, Dr. Omalu left to pursue further education in the US, where he trained as a forensic pathologist under Cyril Wecht, who was notable for his involvement in the JFK assassination inquiries. Wecht had been the first civilian to be given access to the evidence in the JFK investigation and he was also the first person to discover that the president’s brain had gone missing. His new pupil would go on to make forensic discoveries that were almost as surprising and controversial.

A tragic victim

In 2002, Bennet was asked to perform an autopsy on legendary Pittsburgh Steelers’ center Mike Webster, who had died of a heart attack at just 50 years old. Webster was a hall-of-famer who had led the Steelers to four Superbowl victories in the 1970s, and was considered one of the greatest centers in NFL history, but his career post-retirement was tragic and distressing. He suffered from amnesia, dementia, and depression. For long periods, would live in his pick-up truck, refusing offers of accommodation from friends and family. His torment was so severe that he would sometimes use a taser on himself to induce sleep.

Dr. Omalu read the case notes and, although not knowing much about and caring very little for the NFL, he was intrigued. There was nothing particularly surprising about Webster’s heart, and the cause of death was not in question, but what could cause a relatively young, retired athlete to suffer such severe mental difficulties? Bennet sought permission from Cyril Wecht to examine Webster’s brain. Few forensic administrators would agree to such a request but Wecht’s career and experiences were far from conventional and he gave his consent.

Discovering CTE

Progress was slow at first. Bennet examined slice after slice, becoming increasingly obsessed with unlocking the sorry mystery of Webster’s demise. He became concerned that his colleagues would find it unusual - even creepy - that he was staying at his bench until 2 am every night obsessing over one man’s brain. One solution would be to take some much-needed time off, but Bennet instead asked for permission to take Webster’s brain home, and the ever-understanding Cyril Wecht once again granted his permission. Bennet was now able to focus on Webster’s brain in private, and he was so thorough in his work that he ended up spending an estimated $100,000 of his own money on glass slides alone.

Eventually, he found the cause of Mike Webster’s problems, sections of the brain that had been reduced to a gray sludge. Omalu recognized a high concentration of tau proteins, a component part of neurons that are closely associated with degenerative neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. This was an extremely rare discovery in the brain of a 50-year-old man, and given Webster’s history as an offensive lineman in the NFL it had enormous ramifications. Medical science had recorded similar issues in boxers since the 1930s, and this poorly understood condition was referred to as dementia pugilistica - more commonly known as being ‘punch drunk’, but nobody had ever found evidence of brain damage in NFL players until now. Omalu showed his findings to Wecht, and then to scientists at the University of Pittsburgh, All agreed that this was a new and noteworthy discovery. Omalu termed the condition chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and submitted a paper outlining his discovery to the July 2005 edition of the journal Neurosurgery.

Naively, he expected the NFL to be pleased and thank him for his discovery, which would enable them to better protect their most important assets, the players. Instead, the NFL’s own scientists - who sat on the delicately named Mild Traumatic Brain Injury committee - wrote a lengthy rebuttal questioning the validity of Omalu’s research, and demanding that Neurosurgery retract their article. They were unaware of one crucial and highly embarrassing piece of information: Bennet had acquired a second brain of a high-profile NFL player, Terry Long. Terry had committed suicide at 45 years of age and his brain had the exact same patterns of tau proteins as Mike Webster. Bennet wrote a second paper for Neurosurgery detailing his findings, and despite sustained pressure from the NFL, the journal did not reject either paper.

Frustration and vindication

Over the next few years, Omalu encountered more and more cases of NFL players who had died in tragic circumstances. They all showed signs of CTE but the NFL continued to deny a causal link between the disease and the sport. They also continued to dismiss Omalu, refusing to even acknowledge his published research or include him in discussions on the subject of brain injury in NFL players. For someone who had issues with low self-esteem and depression, and who was also a deeply religious man with a strong moral compass, the NFL’s adversarial stance toward Bennet’s work was hard to take. When GQ published a profile of Bennet and his groundbreaking work in 2012, he told them, “I was naive. There are times I wish I never looked at Mike Webster’s brain. It has dragged me into worldly affairs I do not want to be associated with. Human meanness, wickedness, and selfishness. People trying to cover up, to control how information is released. I started this not knowing I was walking into a minefield. That is my only regret."

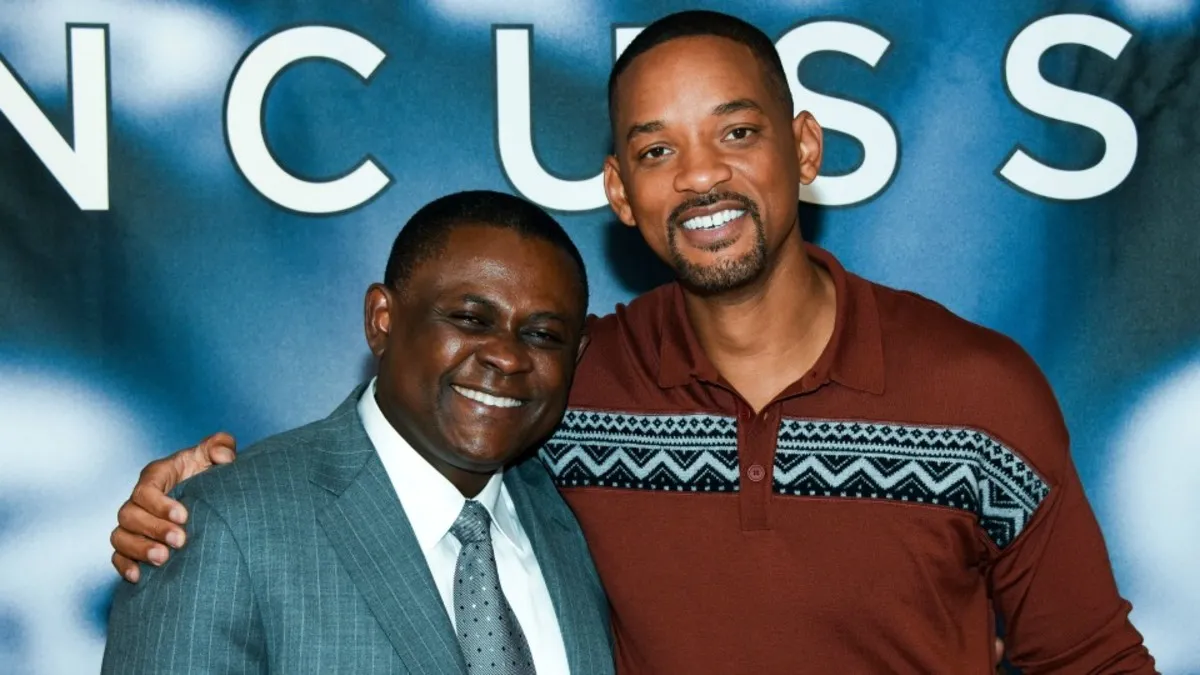

Happier times were to come for Dr. Omalu. The GQ profile brought the story to a wider audience and in 2015 Concussion, a major motion picture based on Bennet’s struggles, was released with Will Smith playing the role of Omalu. His increased profile placed more pressure on the NFL, who until that point had only loosely admitted the possibility of a link between the sport and long-term neurological effects in 2007. In 2016, they were finally forced to acknowledge the reality of CTE. That same year, the American Medical Association awarded Dr. Omalu their highest honor, the Distinguished Service Award.

The vindication of his many years of research must have felt like a victory but Dr. Omalu still faces a great deal of criticism of his work, much of it from individuals who he claims have close associations with the NFL. What cannot be denied is that the impact Bennet’s work has had on the wider world of sport is immeasurable, provoking widespread changes in the concussion protocols of a huge number of team sports, at every level from the professional leagues down to school competitions. There have also been a wide array of compensation cases for players who have been affected by CTE, not just in the NFL but also in sports such as soccer, ice hockey, and rugby. For Dr. Omalu, it is the compensation of those already affected by CTE, and the work being carried out to protect future generations, that is the real vindication of his True Superhero career.

SPYSCAPE+

Join now to get True Spies episodes early and ad-free every week, plus subscriber-only Debriefs and Q&As to bring you closer to your favorite spies and stories from the show. You’ll also get our exclusive series The Razumov Files and The Great James Bond Car Robbery!

Gadgets & Gifts

Explore a world of secrets together. Navigate through interactive exhibits and missions to discover your spy roles.

Your Spy Skills

We all have valuable spy skills - your mission is to discover yours. See if you have what it takes to be a secret agent, with our authentic spy skills evaluation* developed by a former Head of Training at British Intelligence. It's FREE so share & compare with friends now!

* Find more information about the scientific methods behind the evaluation here.

Stay Connected

Follow us for the latest

TIKTOK

INSTAGRAM

X

FACEBOOK

YOUTUBE